History of Basel

From the oldest university in Switzerland to humanism and the Reformation, from the silk ribbon industry to the life sciences, from the Church Council to the First World Zionist Congress – Basel can look back on a long and rich history.

Main source: The Historical Dictionary of Switzerland

Hand axes, Raurici and Romans

The first traces of a settlement in Basel are from the middle Paleolithic period (about 130,000 years ago). In the Bronze and Iron Ages, the banks of the Rhine, the area of the old gas factory (now the Novartis Campus) and the Cathedral Hill (Münsterhügel) stood out as the main settlement areas. The latter area was fortified by the Celts (Rauraci) in the first century BC with the Murus Gallicus (Gallic Wall), whose remains can still be seen near the Münster (cathedral). The Romans founded the Colonia Raurica at the same location, which they extended into a castle in the 3rd century.

Roman Basel

The Romanisation of the region only begins with the Augusta Raurica colony («Roman City» Augst BL) under Emperor Augustus Caesar. After the withdrawal of Roman troops, the Roman population settled in the fort, while the Alemanni spread out to the north of the Rhine and also in Augst. The first mention of the name “Basel” appeared in writing in the year 374, when Emperor Valentinian I stayed at the bend on the Rhine.

A Bishop of Augst/Kaiseraugst and «Basileae» is mentioned in the 7th century. The bishop died in 917 when tribes of Hungarian horsemen attacked the city and destroyed the Carolingian cathedral. The power of the Bishop State was based on donations at the end of the 10th century, and the city became part of the Holy Roman Empire soon afterwards.

Basel in the Middle Ages

Cathedral, Rhine Bridge and Guilds

The bishops of Basel won favour with the Emperor, as can be seen by the foundation of today’s Munster (consecrated in 1019) by Heinrich II. The city government – judicial rights, taxation authority, control over markets, coinage, weights and measures etc. – was exercised by the Prince-Bishop of Basel through officials drawn from the nobility.

In the 13th century, he had a bridge built over the Rhine, and then expanded his authority over Kleinbasel, which was combined with Grossbasel in 1392. At the same time, the local communities secured a considerable amount of autonomy through clashes, sometimes violent, with the Prince-Bishop. The Mayor, the senior Guild Masters and the Council now formed the city government, which ruled the whole of public life.

By largely removing the rule of the bishop, the City also succeeded in repelling the political claims of the Habsburgs. The visible expression of this political and economic advancement could be seen in the representative buildings that were built: the new Town Hall (in 1340), the Arsenal, the Lohnhof, the Hospital and the guild halls.

Basel was not spared when the plague swept through Europe: the epidemic broke out in 1349 and claimed many victims. The population blamed the Jews for this disaster, and burned them all.

A strong earthquake then occurred seven years later. The outbreak of fires in particular caused massive damage in the city. Soon afterwards, the city was surrounded by the outer City Walls, which also enclosed the newly constructed suburbs: The St. Johann Gate, the Spalentor Gate and the St. Alban Gate, as well as the city walls in the «Dalbeloch», can still be seen today.

Council, University and Confederates

In the late Middle Ages, the Rhine City was filled with high dignitaries and foreigners as a result of the Church Council (1431–1448). One of them, Pope Pius II, founded Switzerland’s first university in Basel in 1460.

In economic terms, two annual fairs or trade shows promoted foreign trade, and were recognised by the award of a Market Privilege by the Emperor (1471). In terms of foreign policy, the independence from the Bishop permitted the City to practice an active alliance and territorial policy, which - as in Schaffhausen – led to the membership of the Swiss Confederation in 1501.

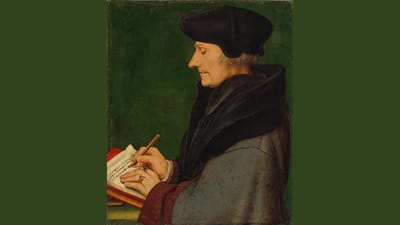

Humanism, Printing and the Reformation

Around the time of the transition to modern times, scholars such as Erasmus von Rotterdam and artists such as Hans Holbein or Albrecht Dürer came to the City. Erasmus had his main works published by the innovative printer Johannes Froben. A prerequisite for this was created in Basel in 1433 with the local paper industry, which blossomed with the Gallizian family around 1500.

The Regiment of the Fifteen Guilds became established between 1521 and 1529. The old ruling class of the aristocratic families and the “Achtburger” who lived on their rents lost their political influence. The new faith, which was significantly helped to break through by the guilds in 1529, was above all spread in Basel by the reformer Johannes Oekolampad. The government closed the monasteries and confiscated their goods, while the converted population destroyed the symbols of the Roman Catholic faith in the «Bildersturm» (iconoclasm).

Basel is a central starting point and centre of influence for the Reformation, which extended far beyond Switzerland and southern Germany. The Reformation movement spread from Basel to various European countries. Basel's importance as a European centre of the Reformation is reflected in the fact that it has officially held the title of "European City of the Reformation" since 2018.

Basel in the 16th and 17th century

Immigrants, Silk Ribbon and Sovereignty

From the mid-16th century, immigrants arrived from Northern Italy and France, in particular religious refugees, including well-known representatives of the silk trade. In addition to commerce, they also operated the spinning, dyeing and weaving shops, used rural homeworkers to produce silk ribbons in the publishing system, and exported them. As a result, Basel developed into a international centre of the silk ribbon industry. This dominated the City until into the 19th century, complemented by a variety of wholesale commerce with cloth, cotton, iron and colonial produce.

Extensive commission and bank transactions secured Basel an increasing important position in international trade. Thanks to the city's success, some religious refugees has already risen into the upper class by the 17th century. At the peace congress following the Thirty Years’ War, the mayor of Basel, Johann Rudolf Wettstein, represented the Swiss Confederation and, in 1648, was able to achieve the independence of the Confederation from the German Empire and the recognition of its sovereignty under international law – the origin of Swiss neutrality.

Oligarchy, Enlightenment and the Common Good

At the time of the «Ancien Régime», the elite of Basel also adopted the French lifestyle and language. Basel merchants opened trading offices in Lyon, Nantes or Bordeaux. The leading families built themselves palaces on the French model (see the "White" and "Blue House") and dressed according to French fashion. The city’s policy also aligned itself to the absolute state power of the «Sun King»: the republic of Basel began to approach the status of an oligarchy («rule of the few») with absolutist tendencies.

Thought and science in Europe began to change fundamentally in the late 17th century. Knowledge began to gradually gain ascendancy over religious dogma. A decisive factor in the new, rational world of the «Enlightenment» was mathematics, in which the Basel academic family Bernoulli excelled – they brought forth a total of nine outstanding mathematicians and physicists. In addition, another genius from Basel, Leonhard Euler, was teaching mathematics in St. Petersburg and Berlin.

On the publishing side, the activities of Isaak Iselin stand out in particular in the Basel of the 18th century. His philanthropic ideas stood behind the «Gesellschaft zur Aufmunterung and Beförderung des Guten and Gemeinnützigen» (GGG: "Society for the encouragement and promotion of good and charitable"), which was founded in 1777. Also initiated by Iselin, die Basler Lesegesellschaft (Basel Readers Association) opened up the debate with the ideas of the time to a narrow circle of people in 1787.

Basel in the 18th and 19th century

Revolution, Mission and Canton Separation

The 18th century strengthened the dominant position of the merchants, bankers and ribbon manufacturers in politics and society. A group of rich merchants led the City with success until the overthrow of the political situation in the Helvetic Republic. When the Helvetic Revolution spread out from Basel and Vaud in 1798, the Old Confederation with its urban authorities and subject territories perished in the fight against the French revolutionary troops (the French Invasion).

While the Basel statesman Peter Ochs drew up a constitution for the Confederation in Paris, the French started to plunder and to politically reorganise the occupied areas. As a result, the population of the Landschaft Basel became the legal equals of the city population.

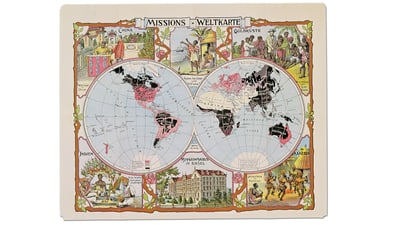

At the start of the 19th century, Napoleon’s economic war against England had a negative effect in Basel, above all on the silk ribbon industry. However, there were also businessmen who made a profit from the inflationary impact of the “Continental System” – such as Christoph Merian-Burckhardt, who acquired an enormous fortune that was used by his son and namesake to establish the Christoph Merian Foundation. Founded in 1815, the Basel Mission is another influential institution which is still active today, working together with churches in Africa, Asia, Latin America and Europe.

The splitting of the canton produced political and financial difficulties: after some violent clashes, the canton of Basel was split into the two half-cantons Basel-Stadt and Basel-Landschaft in 1833.

Industrialisation, Financial Centre and Zionism

Traffic and industrialisation changed Basel in the 19th century: a steamboat moored here for the first time in 1832. Eight years later, the first railway in Switzerland ran on the route between Saint-Louis and Basel, for which a station was opened within the city walls in 1845. Trains were soon travelling to Paris and Frankfurt every day.

In economic life, guild barriers continued to apply for most trades until 1871. Only industry was able to produce without them. Decisive steps towards industrial production in factories were the connection of weaving looms to a waterwheel, and the first steam engine in the Schappe spinning mill.

Basel finally became the largest industrial city in Switzerland in the second half of the 19th century. As a modern financial centre, the City gained international importance with the founding of the Schweizerischen Bankvereins (SBV) (Swiss Bank Corporation) and the Stock Exchange, which remained active until 1996. World history was written with the First Zionist World Congress in Basel in 1897, which started the process for the founding of the State of Israel.

Basel in the 20th and 21st century

Rhine Navigation, Chemical Industry and Commerce

Between the separation of the cantons and the outbreak of the First World War, Basel developed from a small fortified town to a medium-sized industrial city. Modern goods transport started at the Upper Rhine (up to Schweizerhalle) in 1904, and culminated in the building of the St. Johann Rhine harbour and the two docks in Kleinhüningen.

Over decades, commerce has provided the most jobs, above all in the retail trade (Coop). In order to promote the sales of Swiss products, the Mustermesse (Sample Fair) took place in Basel for the first time 1917, from which the Messe Basel has evolved with its many trade fairs.

The most important industry in the meantime, the chemical-pharmaceutical industry, began with the J. R. Geigy pharmacy(from 1758) and/or with the aniline dye production of Alexander Clavel (from 1859). A concentration process has since been underway, which has created the global groups Ciba-Geigy and Sandoz – which merged together to form Novartis in 1996 – and Roche (founded in 1896).

Airport, Life Sciences and Architecture

Due to the geographically limited reach of its policy decisions, cooperation in the Regio Basiliensis has become increasingly important for the Canton of Basel-Stadt in the 20th century. Biotechnology (Life Sciences) became established in the region towards the end of the century. The bi-national airport Basel-Mulhouse (known today as the EuroAirport Basel-Mulhouse-Freiburg) guaranteed connections all over the world from 1946.

In addition to aviation and the Rhine navigation, road haulage with Danzas (now DHL) and Panalpina achieved economic importance in 1991 as the largest private group in the transport sector. When the Schweizerische Bankgesellschaft SBG (Union Bank of Switzerland UBS) and the Schweizerische Bankverein SBV (Swiss Bank Corporation) merged to form the UBS in 1998, Basel – together with Zurich – became the headquarters of a leading global financial institute. At the political level, membership of the European Economic Area (EEA/EWR) was rejected at the national level by the people and the cantons in 1992. Basel-Stadt voted in favour, however, together with French-speaking Switzerland.

Among the cultural milestones of the 20th and 21st century are the establishment of the Basler Orchester-Gesellschaft (1921) and the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis (1933) for early music, as well as the re-building of the Kunstmuseum (1936) and the development of its collection into one of the most important international museums of its kind, together with the Fondation Beyeler in Riehen (1997) and the Schaulager in Münchenstein (2003).

Basel stands out in particular in sporting terms through the world famous Swiss Indoors tennis tournament (since 1970) and the FC Basel (founded in 1893). Its multi-functional stadium «St. Jakob-Park» – designed by Herzog & de Meuron – won the Pritzker Prize, the most prestigious award for architects, for the Basel architects’ office in 2001. Basel has thereby gained a reputation as a leading architectural metropolis at the turn of the millennium.

The Basel Coat of Arms

The Basel Staff is a stylised reproduction of the bishop’s crosier (crook). In 1512, Pope Julius II rewarded the federal towns for their assistance in his war against France. Basel received the privilege of showing a golden bishop’s crosier in its coat of arms, as can still be seen today in the choir of the Leonhardskirche. After the Reformation in 1529, however, Basel returned to the plain, black bishop’s crosier.